A Well-Tempered Thesis

We are so accustomed to hearing and playing any song or piece of music in any key that we can be completely unaware that this flexibility did not always exist. In fact, this may be the first you have heard about it, even if you play an instrument yourself. The difference between true and tempered tuning is, however, very apparent immediately to the ear. Some of the music with which you are very familiar would sound unpleasantly out of tune but for the practice of deliberately tuning some of the strings just wrong enough to sound right.

Dmitri Shostakovich

Each tone can be doubled by a two to one ratio into an octave. It takes a three to two interval to create a perfect fifth. It is the interval of the fifth that makes the biggest difference. Before the prevalence of tempered-tuning, composers could not write pleasing music in just any key, because if a given melody is accompanied by an instrument prepared with true tuning, that is tuned to the exact mathematical frequency (e.g. A is 440 hertz, that is 440 vibrations per second) that defines each of the twelve tones, some melodies cannot be harmonized with a sound that most of us would find acceptable. Also, transposing a piece from one key to another was often simply impossible. This also made it difficult to write music that moves about freely from key to key.

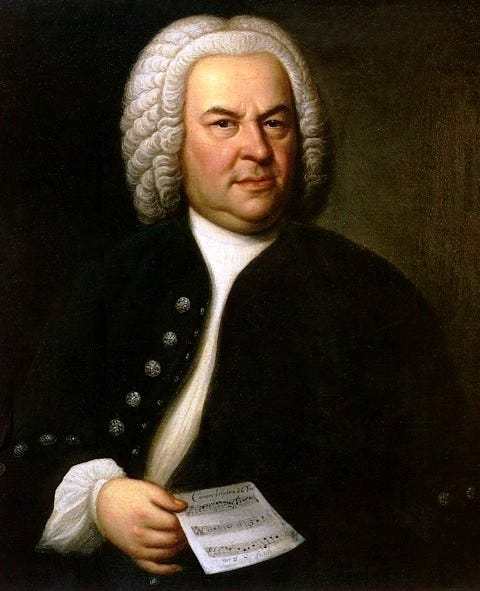

The solution to this problem was first employed during the Baroque era, and among its greatest champions was Johann Sebastian Bach. Like every new idea, it was resisted, causing an inconvenience to notable composers such as Handel and Vivaldi, etc. For the purpose of demonstrating the superiority of tempered tuning over true tuning, Bach composed a total of forty-eight preludes and fugues, Books One and Two of the Well-Tempered Clavier (Keyboard). Each of the two books has one Prelude and Fugue in each of the twelve keys, first major and then minor. So, each of the two books begins with a Prelude and Fugue in C Major, followed by a Prelude and Fugue in C minor, proceeding chromatically up the scale with the twenty-fourth prelude and fugue in each book written in B Minor. In this rich musical library, we have a heritage of magnificent counterpoint, each piece a combination of the composer’s distinctive blend of genius and diligence. These two books were also an argument. Together, they were Bach’s thesis: He argued and proved that tempered tuning provides the opportunity to create greater music, and each piece demonstrates his point.

Although tempered tuning was no longer a subject of argument by the twentieth century, Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his own book of twenty-four preludes and fugues in each key, using a very different approach to harmony consistent with his own era. They are also masterpieces, relating the musical stories that only counterpoint can tell. Preludes and fugues are the freest of classical forms for demonstrating how useful it is to temper the tuning of instruments so that the relation of each note sounds exactly proportional to every other in whole and half steps, even when the music moves from key to key, and that any piece of music can be transposed into any other key. Every tone of the twelve has its major and minor scales that are the structure of keys.

For modern musicians this is basic music theory, so much so that an experienced veteran of musical performance is able, ideally speaking, to play any selection in any key at a moment’s notice. Perhaps the band has practiced a song in A, only to be told at the last moment that a singer wants to sing it in D. One of my recent memories is from a group in Facebook about The Beatles. Because one very opinionated person was confusing the meaning of the word “melody” with the term “chord progression,” I offered a little bit of free education. I pointed out that two songs, Eight Days a Week and You Won’t See Me, make prominent use of the same chord progression. For my efforts I received that emoticon that is a favorite of morons everywhere, the laughing face. Shortly afterwards I was told by a slightly more sober individual that I was wrong because Eight Days a Week is in D, and You Won’t See me is in A. So, I explained that the chord progression is, in both songs, One, Two, Four, One. It is the same progression; only the key is different. That all seems basic enough to modern musicians. But once upon a time it was not even always possible to transpose between every key equally. All it took to improve musical flexibility was tempered tuning - making it just wrong enough to sound right.

************

Below is an old video, one of me playing the Prelude and Fugue in A flat Major from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, Book One. It does not have the visual production quality of my current videos, but it has sufficient audio quality. My hair had color to it back then, in 2012.

Thanks for the history lesson.